Her Unique Edge: How a Mother Helped Her Daughter with Down Syndrome Live a Normal Life

Her Unique Edge: How a Mother Helped Her Daughter with Down Syndrome Live a Normal Life

Tanya was not predicted to have the best fate. In the maternity hospital, the girl’s heart stopped, and her mother, Ekaterina, had to undergo an emergency C-section. Tanya was resuscitated for a long time and then placed on a ventilator. The doctors told Ekaterina that her daughter had Down syndrome and recommended that she give her up. “I was strongly pressured until I had a nervous breakdown and lost my milk,” Ekaterina recalls. From Tanya’s first day, she had to fight for her daughter’s rights—the right to live, develop, learn, and be a normal child, not a child with a diagnosis.

Fighting for the Rights of People with Down Syndrome in Belarus

Now, Ekaterina Filonets is fighting not only for Tanya’s rights but also for the rights of other people with Down syndrome in Belarus. She is the chairperson of the “Down Syndrome. Inclusion” association. We talked about what the association has achieved in 5 years of work, what difficulties Ekaterina faced, and how her personal experience helps other parents.

“Parents often don’t know how to behave with children with Down syndrome”

“When Tanya was 2.5 months old, we got to the Early Intervention Center in Minsk. There, for the first time, someone told me, ‘I congratulate you on the birth of your daughter!’ It sent shivers down my spine. At that moment, I realized for the first time that I was a mother.”

Now, when mothers of children with Down syndrome turn to me, I first congratulate them on the birth of their child. For some reason, this is often overlooked. When you have a special child, people don’t know how to behave or what to say.

Parents themselves often don’t know how to behave with their child—what to do and where to turn. Our organization works to help them. We advocate for the full inclusion of people with Down syndrome in all spheres of society. We do a lot to ensure that children with the syndrome are not abandoned in maternity hospitals.

Our Story

Together with the Early Intervention Centers, which operate with the support of UNICEF in Belarus, we conducted training for neonatologists, pediatricians, and maternity ward doctors on how to properly inform mothers about the diagnosis. We prepared brochures for maternity hospitals with information that would not scare them. We left our contacts to support mothers right after they gave birth.

Another goal of the organization is psychological support for parents. We let parents feel that they are not alone. When a child with Down syndrome is born, many parents think they are the only ones affected. At that moment, I, as a mother, or another mother who has gone through this stage, say: “Everything will be fine, really. Look at me. Here is my story. You are not alone. There are many of us. We can go through this stage together.”

Here is My Story

I gave birth to Tatiana very early, at the age of 20. It was a planned pregnancy. Both my husband and I were fully prepared for it—with vitamins and tests.

All ultrasounds were perfect. But I learned about the syndrome after Tatiana’s birth. When I was in the hospital for preservation, Tatiana’s heart stopped, and I had to have an emergency C-section. She was resuscitated for a very long time and was on a ventilator. There was little chance she would survive.

I was told some myths about Down syndrome and neurology. Although I understand that Down syndrome plus neurology is not a rosy picture.

When we took Tatiana home, we didn’t know what to do with her. At that time, there wasn’t as much information on the internet as there is now. There were no organizations, and doctors knew little about the syndrome.

I didn’t try to find someone to blame or panic. I have a character that, when faced with difficulties, it’s easier for me to look for solutions than to freeze. I understood that I had a problem. I had a child who needed help. I looked for any information.

By chance, I learned that there were Early Intervention Centers in Minsk. I was lucky—a spot had just opened up for classes. As long as I give interviews, I will thank these people. In fact, everything that Tatiana and I have is largely due to the workers of the Center. No one in my life has ever given me as much support as these people. The specialists at the Center gave me an idea of where to go next. Undoubtedly, there was very intensive weekly work for 3 years.

We kept a close eye on Tatiana’s health and my psychological state. We discussed every next step. So, we decided that Tatiana needed a team—she was developing well. From the age of 2 to 3, I sent her to a preschool preparation group for a few hours. After that, we decided that Tatiana would go to kindergarten.

Unfortunately, the Center for Correctional and Developmental Education and Rehabilitation (CICDER) at that time offered only special groups in special kindergartens. When Tatiana went to a private kindergarten, she made progress in speech development. I saw how important it was for her to communicate with her peers. I wasn’t offered anything, so I enrolled her in a regular kindergarten. I hid the diagnosis: I asked the doctor to write it in code, not in letters—parents have the right to do this.

Tatiana went to a general group with 35 children. There were no special conditions or tutors. I brought a description and conclusions from the CIC and the private kindergarten and told the teachers: “Perhaps I didn’t do the right thing by hiding the diagnosis. But let’s try, I beg you. If you have difficulties that we can’t overcome together, I’ll take Tatiana away. Just give her a chance.”

Everything worked out great. Tatiana finished kindergarten with the other children. There were no questions from parents, teachers, or the headmistress.

Then the question of school arose. There were no precedents for a child with the syndrome going to a regular school in a regular class, as I wanted. I managed to get a referral to an integrated class, but I had to find the school myself. I visited many schools in Minsk, but I was told: “No, no, we won’t do that.”

Chance helped. UNICEF organized a conference on inclusion. There were directors of different schools, and active parents were invited. I took the floor. I understood that we had a problem, and I had to defend my child’s interests. Tatiana is an active child who needs adaptation in a team. At that time, she was well prepared for school: she could count, write, and read. But we were still not accepted anywhere except for a special school.

I really liked School No. 25 at the conference. The director talked about integration. I thought—I’ll call there and make an appointment. The director saw me at the appointment and smiled. She says: “I know why you came—you want to go to our school. Let’s try! We didn’t have such experience. But I like your life position. I think everything will work out with us.”

A teacher looked at Tatiana, and the training began in a regular class on a regular program. Although, in fact, she was not supposed to study most of the subjects. It’s true that the relationship with the after-school teacher didn’t work out. She didn’t accept Tatiana at all and saw only the diagnosis in her. There were many unpleasant situations. At that moment, I sought professional psychological help.

After the first grade, I finally fully accepted Down syndrome. I realized: “Yes, Tanya will be different, yes, she will not be like other children. But that’s good. It’s her unique edge.”

Tanya is now finishing the 9th grade, and I have never regretted my decision to send her to a regular class.

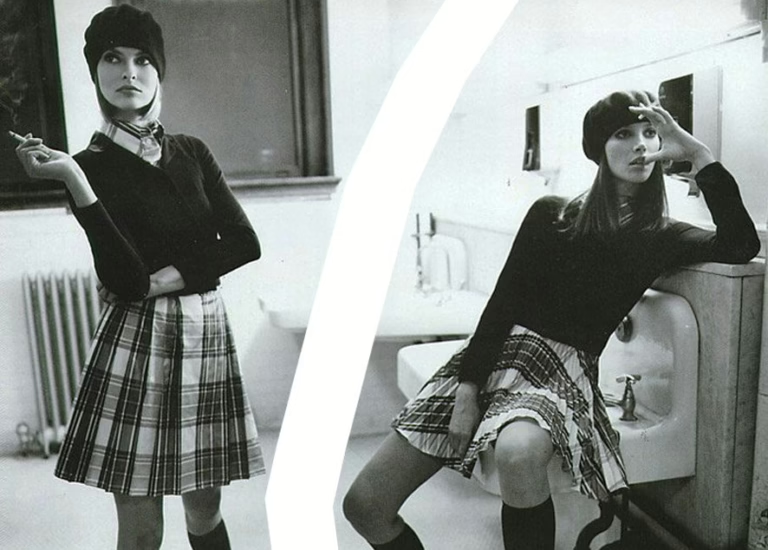

In addition, Tanya graduated from a modeling school, received a diploma, and even worked as a model for some time before COVID-19. She was paid for it and had a contract with a modeling agency. She even opened Belarusian Fashion Week.

Tanya also does yoga, goes to the gym. She studied DJing in courses, but unfortunately, COVID-19 did not allow her to finish.