Sergey Balenok’s Artistic Universe: A Journey Beyond Reality

Sergey Balenok’s Artistic Universe: A Journey Beyond Reality

Is it a burst of fantasy or the magic of dreams? Is it the symbolism of images or perhaps “philosophy in pictures”? Sergey Balenok, a bright and unique artist, draws viewers into his world, inviting them to interpret his visual and figurative associations individually. “I don’t paint familiar objects. I depict impressions, emotions, and memories that are inherent to each of us,” says Balenok. In an exclusive interview, the Belarusian artist shares his insights on life, creativity, and his inner calling.

Daily Life and Creative Process

Sergey Balenok’s day is not dictated by a strict schedule but rather by his internal state. Each day brings different moods and inspirations. Without a genuine impression or an internal “sensation” of an image, starting work is meaningless. For Balenok, graphic art requires concentration and focus, and he finds the afternoon to be the best time for this. Quality always trumps quantity; he might work only once or twice a month, but he does so with utmost seriousness. Painting, on the other hand, is reserved for weekend mornings when he feels the colors most acutely, their resonance and depth.

Balenok does not adhere to specific stylistic directions; he paints as he sees. In this regard, he feels close to impressionism, not in terms of “capturing” but in terms of “impression” from what is seen or heard. It’s one thing to “paint” specific objects in an impressionistic manner and another to feel the intrinsic nature of color and resonate with the elements of the surrounding world.

Professional and Creative Positions

There is a clear distinction between an artist and a Creator, and it’s not about professionalism or skill. The main difference lies in the vision of the surrounding world. The modern art market is extremely diverse, and buyers often don’t know what they want to acquire. In his work, Balenok depicts what is common to all people, regardless of race, nation, or gender. Ultimately, we all experience similar feelings and sensations.

During training, the academic school is crucial but only at the initial stage of development. Further, the artist should move away from templates and strive to reflect an individual vision of the world, whether external or internal. Balenok does not depict specific or familiar forms and objects. For him, impressions are essential, even from color. For example, yellow does not necessarily mean the sun; it can evoke warmth, the sincerity of a moment, or represent a memory of a joyful day.

Philosophy in Pictures

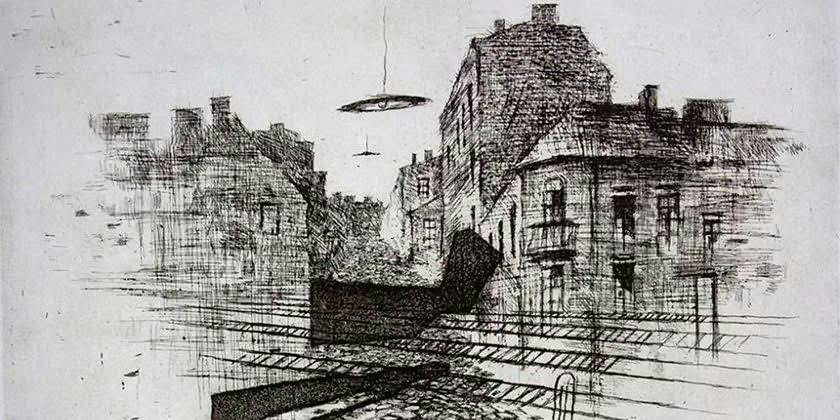

Balenok’s works can be described as “philosophy in pictures.” He has met many people who perceive the world as he does. Different words can describe the same subject, and the same applies to graphics. Behind a familiar lump of snow or the image of a stuffed animal, there may not be snow or a stuffed animal at all. It could be sadness, melancholy, or loneliness. Everything depends on the internal context. Balenok often spends a long time coming up with titles for his works. When creating a “picture,” he never follows a strict plot or plan; it’s an improvisation.

As for philosophy, he does not like to impose his opinion on the public because it can be biased or overly subjective. He prefers to let the viewer draw their own conclusions and form their own understanding of what they see.

Literary and Artistic Influences

Balenok has worked in graphic art, illustrating books by Jules Verne, Kurt Vonnegut, Mikhail Bulgakov, and even the poetry of Joseph Brodsky. His choice of such diverse authors was influenced by his work at the “Universitetskoye” publishing house, which specialized in fantasy. Illustrating poetry is extremely challenging, but Brodsky represented a generalized idea of poetry. With Kurt Vonnegut, Balenok was particularly lucky; his graphic works from the 1980s attracted the attention of publishers, who chose his ready-made sketches for Vonnegut’s works. He appreciates Bulgakov for his atmospheric and unbiased creativity, intelligence, and excellent taste.

Balenok’s literary preferences include Dostoevsky, especially “The Idiot,” Franz Kafka’s “protokol” prose, Jack London, Vladimir Makanin’s “Where the Sky Met the Hills,” and Erich Maria Remarque’s “All Quiet on the Western Front,” “Three Comrades,” and “Arch of Triumph.” Among Belarusian authors, he values Vladimir Korotkevich’s “The Wild Hunt of King Stakh.” His favorite artists include El Greco, known for his excellent drawing skills and sense of color, Marc Chagall for his stained glass works, and Andrew Wyeth for his depth and philosophy.

Symbolism and Personal Reflections

Balenok does not consider himself a symbolist by nature. He is a city person and does not believe in superstitions. What can be seen in his “pictures” is his subjective reflection of reality, which sometimes coincides with the vision of other people. He does not strive to depict contrived objects or create rebuses. His symbolism is very conditional and comes from intuition.

The electric lamp is a recurring motif in Balenok’s work. Since he can remember, the electric lamp has been present in his life, symbolizing artificial light that he constantly wanted to replace with something brighter and more alive. Over time, he achieved this in his paintings, but in graphics, he could not get rid of this persistent image. The lamp has become a part of his life and often appears in his “pictures.” Other recurring motifs, such as overturned coffee cups or fragments of the old city, are associated with his childhood and youth in Lviv.

For further reading on Sergey Balenok, you can visit his Wikipedia page.