Unraveling the Mystery of Sleep: Insights from a Pioneering Scientist

Unraveling the Mystery of Sleep: Insights from a Pioneering Scientist

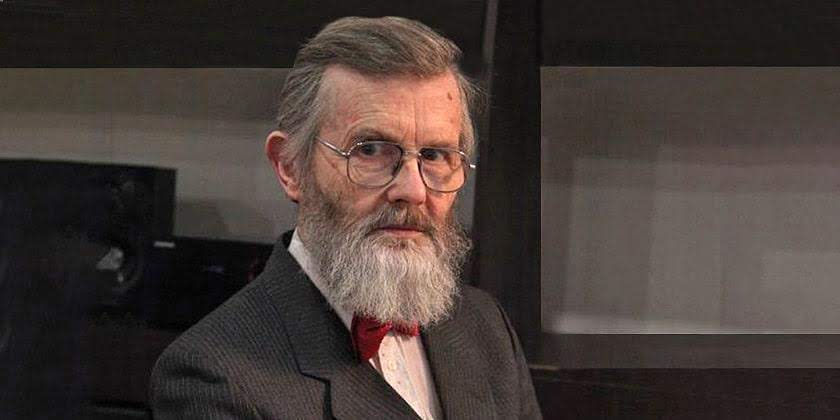

Since the dawn of humanity, we have been trying to unravel the mystery of sleep. Why do we sleep? What happens to our bodies during sleep? Why do some people dream in color while others dream in black and white, and some not at all? What do our dreams mean? Why does a person die faster from lack of sleep than from lack of food? Recently, a revolutionary hypothesis by Dr. Ivan Pigarev, a Doctor of Biological Sciences and the chief researcher at the Laboratory of Information Transfer in Sensory Systems of the Institute for Information Transmission Problems of the Russian Academy of Sciences (RAS), turned all scientific notions of sleep upside down. We contacted the scientist to learn more about his discovery, which could change our lives.

Sleep: A Misunderstood Necessity

Dr. Pigarev, it was previously believed that sleep is necessary for rest and physical recovery. What conclusions have you drawn? What are the functions and tasks of sleep?

For a long time, it was believed that sleep is necessary for the brain to rest. It was well known that during sleep, the transmission of signals from the environment to the brain is significantly impeded or even stops altogether. Simultaneously, the transmission of commands from the brain to the body’s muscles ceased, leading to their complete relaxation, especially in certain sleep phases, making voluntary movements impossible. This created the impression of the brain being completely isolated from the environment during sleep, which was naturally seen as the brain’s rest after a day’s work. Vivid dreams, which people reported after sleep, confirmed the conclusion about the dominant connection between the state of sleep and the processes occurring in the brain.

However, the first electrophysiological experiments, which recorded the activity of brain neurons during natural sleep, challenged this view. It turned out that brain neurons not only do not rest during sleep but often behave more actively than in a waking state. Moreover, in warm-blooded animals during sleep, neurons in the brain cortex switch to a very similar mode of operation called the “burst-pause” mode. Neurons periodically become strongly activated for a short time and then fall silent, and this pattern continues throughout the first phase of sleep, which was called slow-wave sleep. During wakefulness or the second phase of sleep, the so-called rapid eye movement (REM) phase, these waves stop, and neurons switch to non-rhythmic high-frequency pulsation. It became clear that sleep is not a rest for neurons but some active activity whose meaning remained a complete mystery.

A Revolutionary Hypothesis

As early as the end of the 19th century, before the first electrophysiological experiments, Dr. Maria Mikhailovna Manaseina attempted to exclude sleep from an animal’s life and see what would happen. Then, this same technique was applied in the laboratory of Academician K. M. Bykov in Leningrad in the 1930s. And only after a large cycle of similar works done in the laboratory of Allan Rechtschaffen in the USA in the 1990s, attention was drawn to the result of these studies. The result was simple: after several days of sleep deprivation, animals died from multiple disorders in all internal organs. Surprisingly, the brain was the most resistant to sleep deprivation, in which no visible changes were found even in animals that died from sleep deprivation.

A paradoxical situation arose. Our visceral theory of sleep was designed to resolve all controversial points. We suggested that the same parts of the brain cortex and the same neurons that, in the waking state, analyze signals coming from the outside world (visual, auditory, etc.), in the state of sleep, switch to analyzing signals coming from the internal organs of our body.

For the past 15 years, at the Institute for Information Transmission Problems of the Russian Academy of Sciences, we have been trying to experimentally confirm our hypothesis—and we have succeeded. Neurons in various parts of the brain cortex, which in the waking state were associated with the assessment of the body’s position or signals coming from the external world, began to respond during sleep to signals coming from the stomach, intestines, heart, and lungs. It became clear that the disruption of normal sleep deprives the internal organs of central nervous regulation and soon leads to pathological changes in their activity. Thus, the state of sleep, which some people consider a meaningless waste of time, actually maintains the efficiency of the entire body, including the effectiveness of the brain itself, the most important visceral organ of the animal body.

Sleep Across the Animal Kingdom

Since we are talking about animals, it is known that a giraffe sleeps for 2 hours, a sea lion for 6, a dog for 10, a squirrel for 14, and a koala for 20-22 hours a day. Why does a person need 8 hours of sleep?

First of all, all these figures should be treated with great caution. How to assess the state of sleep? A person is lying on the couch with their eyes closed. Are they sleeping or just thinking about something? We cannot answer this question based on superficial external observation. We can record an electroencephalogram. But this is not a salvation either. In laboratory conditions with an uncomfortable position and irritating electrodes, animals can sleep less than normal. If we record remotely, without wires, in natural conditions, it turns out that the pattern of electrical activity in active wakefulness often does not differ from the pattern of deep sleep. If we study the sleep of domestic animals like dogs, they do not need to get their own food, and out of boredom, they can sleep much more than the minimum subsistence level. The duration of sleep can depend on the nature of nutrition. For example, if an animal is adapted to eating one specific type of plant, then maintaining the efficiency of the digestive system may require less time compared to animals with a mixed type of nutrition. There are many such factors. Well, koalas eat only eucalyptus leaves, which they live on and which are in full abundance around them. They can simply sit still due to the complete absence of the need to move to another place and digest the eaten leaves, and from the outside, this looks like a very long sleep.

The duration of human sleep is determined by age, gender, and health status. There is no single figure that is valid for everyone. Everyone should listen to their body. Sleepiness arises when signals from any of the systems of internal organs begin to indicate that the parameters of the organ’s work are beyond the normal range and require the brain’s intervention to eliminate malfunctions.

The Consequences of Sleep Deprivation

It is known that in 1965, schoolboy Randy Gardner, who decided to conduct an experiment, did not close his eyes for 11 days, for which he entered the Guinness Book of Records. What are the consequences of chronic sleep deprivation? And what are the consequences of long-term sleep deprivation?

The consequence of long-term sleep deprivation is the inevitable death of the organism. Randy Gardner, as far as I know, was the last person to have this record registered. Further records in this category were no longer registered precisely because of the strongest harm to health. On the fifth day, this schoolboy already had the most serious mental deviations. Before that, there were undoubtedly disorders in the work of the gastrointestinal tract. But this side was simply not paid attention to, since in those years no one had yet thought about the connection between sleep and the work of internal organs. The long-term consequences of this unwise record.

For more information on the importance of sleep and its impact on health, you can visit the Sleep Foundation.