A Glimpse into the Life of Vladimir Korotkevich: A Personal Perspective

Introduction

Upon hearing the address, I realized this wouldn’t just be an interview with Vladimir Korotkevich’s niece, but a visit to his very own space. I was thrilled beyond words. How would you feel if you were about to step into the room where “The Black Castle of Olshany” was written?

Epitaphs and Dedications

I’ve never quite understood the purpose of epitaphs, even though I’ve used them myself from time to time. Dedications, on the other hand, are a different story. I often feel compelled to dedicate my texts to someone.

But let’s return to epitaphs. While preparing this text, I unexpectedly came to the opposite conclusion: sometimes, an epitaph is absolutely necessary. At least, in this case, I couldn’t do without one. So, I present it here in an unconventional place and manner.

Epitaph

Alena is one year and nine months old. But she’s already a big girl. After all, one should judge not by age, but by what one has accomplished. And she’s already a person because she learned to walk upright long ago. And she’s also learned to express herself somewhat, and her relatives, at least, understand her. And there’s one more thing, the most important: if someone makes a move to harm a cat, a dog, or a person, a desperate, pleading cry is immediately heard:

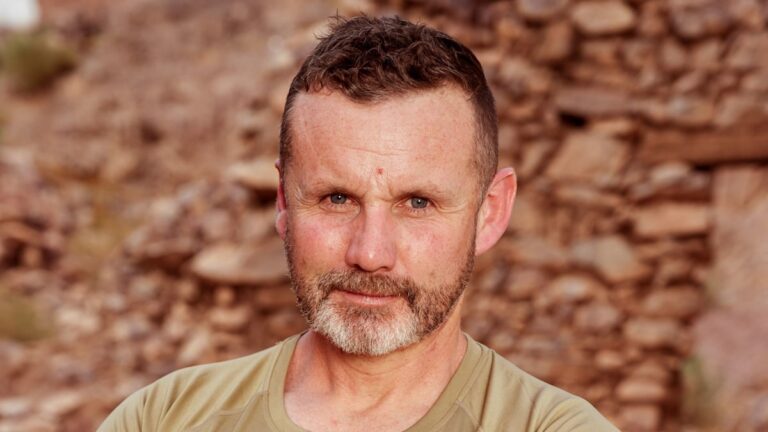

Vladimir Korotkevich with his niece Alena

“I tseba.”

This means “don’t.” So, the main thing that makes a person is already there.

Alena has huge, saucer-like blue eyes, a slightly protruding lower lip (it’s clear that her character will be a bit capricious and independent), a body taut as a ball, and legs that stomp around the house, garden, and yard all day. She’s a typical mischievous child. And that’s very good because it’s from such children that worthy people emerge.

Alena has a mother, a beautiful, plump woman, a father who stayed in their town to fly “airplanes,” and grandparents who adore her. Besides, she has an uncle who thinks too much about world problems. This uncle loves to babysit and pamper her, and feeling her warmth on his lap, he remembers a lot. And then his face becomes emaciated and sadly handsome. And the grandmother, seeing this, hurries to pass by him as if she doesn’t see him, and talks about nothing with her daughter, Alena’s mother. Sometimes, Alena’s mother can’t stand it and takes her daughter away from her uncle.

“Why do you always sit here with her?”

“Because I don’t have my own.”

Signature

Of course, every epitaph has its signature. It can’t be otherwise. The signature under the given epitaph should be as follows: Vladimir Korotkevich. “How Idols Are Overthrown.”

Part One: Antipastos

No matter how much you try to put yourself in the shoes of a famous person’s relative, you won’t succeed. You can imagine, but you can’t feel. You can only notice in numerous observations that the attitude towards the famous from their relatives is less pathos-ridden. That is, more natural.

In Vladimir Korotkevich’s office, I ask Alena Sinkevich not about the classic of Belarusian literature, but about her mother’s brother, her uncle Volodya.

“Yes, for me, Vladimir Semyonovich is, first of all, my uncle Volodya. I remember him from my childhood when he visited us in a military town near Chelyabinsk, where my father served as a military pilot. He was so big, handsome, cheerful – for us, it was a holiday. He probably worked a lot because a slit under the door to his room was lit even at night. But he also rested well: he walked around, skied with my sister (and I was little and jealous). And in the summer, we met in Orsha, in my grandmother’s house. There was a wonderful place: a big garden, the Dnieper nearby. Next to the house stood a shed, on the attic of which was Korotkevich’s “office.”

In the early 1960s, my uncle received a one-room apartment in Minsk, on Chernyshevsky Street, and took his mother, my grandmother, to live with him. The large room was divided by a wardrobe, one half of which was my grandmother’s, and the other was Korotkevich’s “office.” Then we started coming to Minsk for the holidays. In 1967, the Korotkevichs moved to a two-room apartment on Veri Khoruzhei Street. Here, my uncle already had a separate room and a real office. The Korotkevichs’ house was always hospitable. Friends and acquaintances, various interesting people gathered here. They talked, argued, sang, read poetry. The atmosphere of these evenings was impressive. My uncle read his and others’ poems very well. It was as if some light emanated from him. In my head, his “Fountain of Tears” still sounds (the reader can also hear it by typing here).

In 1971, we moved to Minsk and lived with the Korotkevichs for several months until we got our own apartment. I was in the eighth grade then. Studying the Belarusian language was not mandatory for children of military personnel. Of course, my uncle was indignant: you must, he said, learn the language. But my mother insisted that the certificate should not be spoiled by an extra “C,” and that I would not have time to learn the language well anyway. So, it turned out that I did not study Belarusian. The first book by Vladimir Korotkevich that I read was “Chazenia.” It was published in Russian when we still lived in Chelyabinsk. I was twelve or thirteen years old. What I read captivated me: high and pure love at that age could not but impress. Besides, I was interested that it was written by my uncle.

Already in Minsk, I began to read all the works of Korotkevich that were translated into Russian. My uncle did not force us to speak Belarusian and spoke with us in Russian himself (he usually spoke to people in the language in which they could answer him). But he always told me that I needed to learn to read in Belarusian. But did I listen? I did what was convenient for me… The very first of his works that I read in the original was “Leonids Will Not Return to Earth” (a work that was published under the title “We Cannot Forget,” because Leonid was then the leader of the country). At first, it was difficult, but there was no translation, and I really wanted to read it. And when I read it, I understood: I need to read in Belarusian. And I began to reread everything that I had read before in translation.

…We came to this apartment on Karl Marx Street (the house is called “monoLIT” because many writers lived and live in it) to visit my uncle. It’s a shame that I didn’t perceive him then as a future classic of Belarusian literature. Now I often think: how much could have been asked and even recorded… When his wife was no longer there, it was hard for my uncle to stay alone, and after some time, my parents moved in with him. And after his death, they carefully preserved everything that was here for twenty years. Now my husband and I live here, and it’s our responsibility. People who knew Vladimir Semyonovich, researchers of his work, and philology students come here to “Korotkevich’s” office. Some say: “Maybe it’s good that there’s no museum here. In the atmosphere of an ordinary apartment, the presence of the owner is felt.” It’s been over thirty years since he passed away, but at some point, you seem to hear his voice from the office: “Leshka, stand before me, like a leaf before the grass.”

Part Two: Excursion

There are many books in the office that can be best described as “tomestones.” Reference books, encyclopedias, multi-volume editions…

“Well, the books here are different. First, in Soviet times, it was not so easy to get the books you wanted. Rather, books that could be, in the language of that time, “obtained” appeared. But I think there are no random books that Korotkevich would not like or that would not be needed for work. There is Russian and foreign classics, books by Belarusian authors (many with dedicatory inscriptions), books on history and art (including Polish and Czech editions). There are books gifted to him even during his student years. There are also works by Vladimir Korotkevich himself. Almost every book has his ex-libris.”