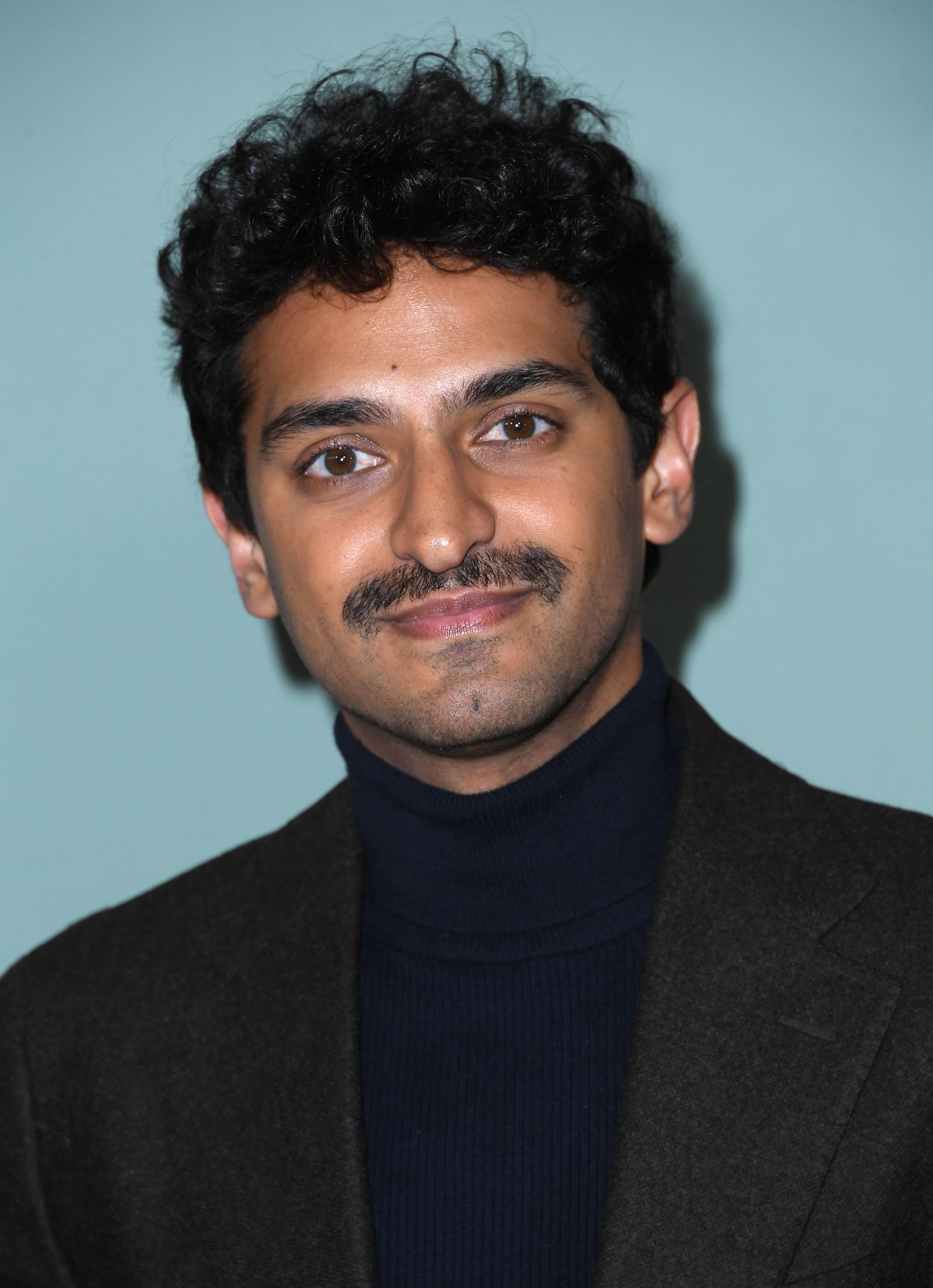

In A Nice Indian Boy, actor Karan Soni questions why two gay men can’t have their own DDLJ

In A Nice Indian Boy, actor Karan Soni questions why two gay men can’t have their own DDLJ

“How will I ever bring someone home to my family?”

That was one of the first thoughts actor Karan Soni had after coming out to his parents at 19. It is also the nexus of his new film, A Nice Indian Boy. “It took my family six or seven months to come around after I told them, but even when they did, they wouldn’t talk about it. They’d ask my sister about her love life while studiously avoiding asking me about mine, and I’d think, ‘Well, I don’t want to re-traumatise them’. Coming out isn’t a one-and-done deal; there are waves. But you know that already.”

I do know that. As a brown bisexual woman, I understand the intersection of brownness and queerness at the heart of this film well. I’d understand it even better if I could watch it, I complain to Soni.

“I scoured the entire internet and nary a clip,” I grumble.

“I know, I’m sorry!” He smiles sheepishly. “We’re releasing it in the US next year, fingers crossed.”

For now, the film is on its festival circuit, showing at BFI London, NewFest, Hamptons International Film Festival, SXSW and others. It’s already a hit with the queer South Asians who have seen it. Based on the play by Madhuri Shekar, A Nice Indian Boy is the story of an Indian boy who brings his white American fiancé to meet his very desi parents. Chaos and comedy ensue.

The film isn’t a cookie-cutter adaptation. Soni and director Roshan Sethi made sure of it by personalising the script. The good Indian boy is a doctor (the NRI mummy-daddy dream) instead of a techie (the millennial NRI cliché). “Roshan also changed the white wedding planner to a big-deal Delhi wedding planner. Like those awful masterjis who yell at their clients but have the best vendor hook-ups,” Soni laughs. “The character turned out to be wild. He keeps calling it a ‘homo wedding’ and it’s a riot.” They also tweaked it to make it more current and authentic. “Roshan would often say, ‘Remember that thing your mom said to you? Let’s put that in.’ It made it feel more real.”

Sadly, ‘real’ brown characters, especially queer ones, are still a scarce resource in Hollywood.

“Do you think it’s because in a mostly white writer’s room, a brown character themselves seems token enough? Having them be queer too perhaps seems too niche?” I wonder aloud.

“A hundred per cent,” Soni agrees. “When I started in 2010, all the studio execs I knew were white. And that’s only changed a little.” A Nice Indian Boy, the 35-year-old actor explains, “is financed by two companies that are run by white people, because they have money. They wouldn’t have come up with this idea themselves. They’d feel it wasn’t their story to tell.” Luckily, for everyone involved, a producer’s sister had dated an Indian guy and there had been tension with bringing him home. “Roshan and I often wonder, ‘What if she hadn’t dated that guy?’ There’d be no touch point, no movie.”

It isn’t easy to push for your story to be told—or told right—explains Soni, recounting his experience playing Pavitr Prabhakar (the Indian Spiderman in Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse). “The writers Phil [Lord] and Chris [Miller] are amazing, but they were so focused on Pavitr’s visuals that the character didn’t end up having much of a personality. I was too scared to say anything about it.” Luckily, someone else did. “Some animators on the movie were Indian and they set up a call with the writers to say: ‘We’re disappointed. We expected this character to be more.’”

The writers, remarkably, had no ego about it. “They said, ‘It’ll cost money, but let’s do it over.’ Hasan [Minhaj], me and a few other brown writers did a mini writers’ room. They showed us the character sequences, which never happens when you do voiceovers, and the character was better for it.”

Finding that bridge between cultures has been a big part of Soni’s life as well as this film. “Honestly, Roshan and I just wanted to make a Bollywood film in Hollywood,” he laughs. “Hollywood people love to say, ‘I want to watch Bollywood’ but they get bored or don’t understand it. Someone asked me, ‘Is RRR a gay movie? Because the two men hold hands in that song,’ and I said, ‘No, that’s friendship!’”

A Nice Indian Boy is a love letter to Bollywood—and its Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge (1995) homage is only the beginning. Apparently, Jonathan Groff singing ‘You’ll Be Back’ as King George III in Hamilton (2020) has nothing on his rendition of ‘Tujhe Dekha To Ye Jana Sanam’. “Even the structure of the film is classic Bollywood,” Soni says. “In typical Hollywood romcoms, the characters can’t be together till the end. But here, the characters get together partway and the conflict is family acceptance.” Family is such a key part of a desi love story—and conspicuously absent in the Hollywood version. “Take Sex & The City. We have six seasons and a movie. Who are Carrie’s parents?” he laughs.

While the movie has been unanimously praised by critics in first reactions at film festivals and even received a rare 100% rating on Rotten Tomatoes, it made Soni realise that the influence of cinema hasn’t been able to eradicate the stigma of being queer. The actor recalls a comment made at a film festival that he hasn’t been able to shake. “At DesiFest, which is mainly a South Asian audience, a man told me, ‘I wish you had made this movie realistic. In real life, I’m not going to get married and my parents won’t come to my wedding.’ It broke my heart.”

The big fat Indian wedding feels so out of reach for queer couples not only in India, where same-sex marriages are still unlawful, but also abroad, where brown parents don’t want to lose that gossamer-thin tether to their culture and traditions. “There’s this scene in the movie where my parents say, ‘Okay, so you’re going to have a gay wedding? You’ll wear matching suits and you’ll go to a church?’ To which my character says, ‘No, I want an Indian wedding.’ And they can’t accept that because the idea of inviting their friends and family to watch two men walk around the mandap is so strange.”

The ingrained queerphobia, in fact, runs so deep that the crew even had trouble finding a pandit to fake-bless the movie wedding. “Most pandits refused to work on this, and we thought, ‘Wow, the conflict has turned up in real life,’” Soni recalls. “It was the same message: ‘The Indian shaadi is not for you.’” The words of one pandit still rankle Soni. “He seemed so warm at the start, but when we told him about the ceremony, he said: ‘I won’t help two fags get married.’”

Soni thinks the film is a hopeful step towards changing hardwired mindsets. “That’s what I love most about the film—that it can help. It would’ve helped me as a kid to show my parents 10 years ago. Maybe now it’ll help someone else.”

Also read:

Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse taught me to accept the things I cannot change

Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge: Would Raj and Simran still be together today?